🩺 Thankful to our Veterans in more ways than one.

From Battlefield to Operating Room: How Military Patients Shaped the Birth of Plastic Surgery

Plastic surgery today is often associated with cosmetic enhancements—nose reshaping, facelifts, and aesthetic tweaks. Beauty! But plastic surgery’s origins are far more profound, rooted not in beauty but in survival. The field was forged in the crucible of war, where military patients—scarred, burned, and broken—became the unwitting pioneers of reconstructive medicine. Their suffering demanded innovation. Their resilience inspired transformation. And their stories laid the foundation for one of the most impactful medical disciplines of the modern era.

⚔️ The Brutality of War and the Rise of Facial Trauma

Before the 20th century, facial injuries were often considered untreatable. Soldiers who survived devastating wounds to the face were left disfigured, socially isolated, and psychologically shattered. The trench warfare of World War I introduced new weapons—machine guns, artillery shells, and poison gas—that caused unprecedented facial trauma. These injuries weren’t just life-threatening; they were identity-threatening.

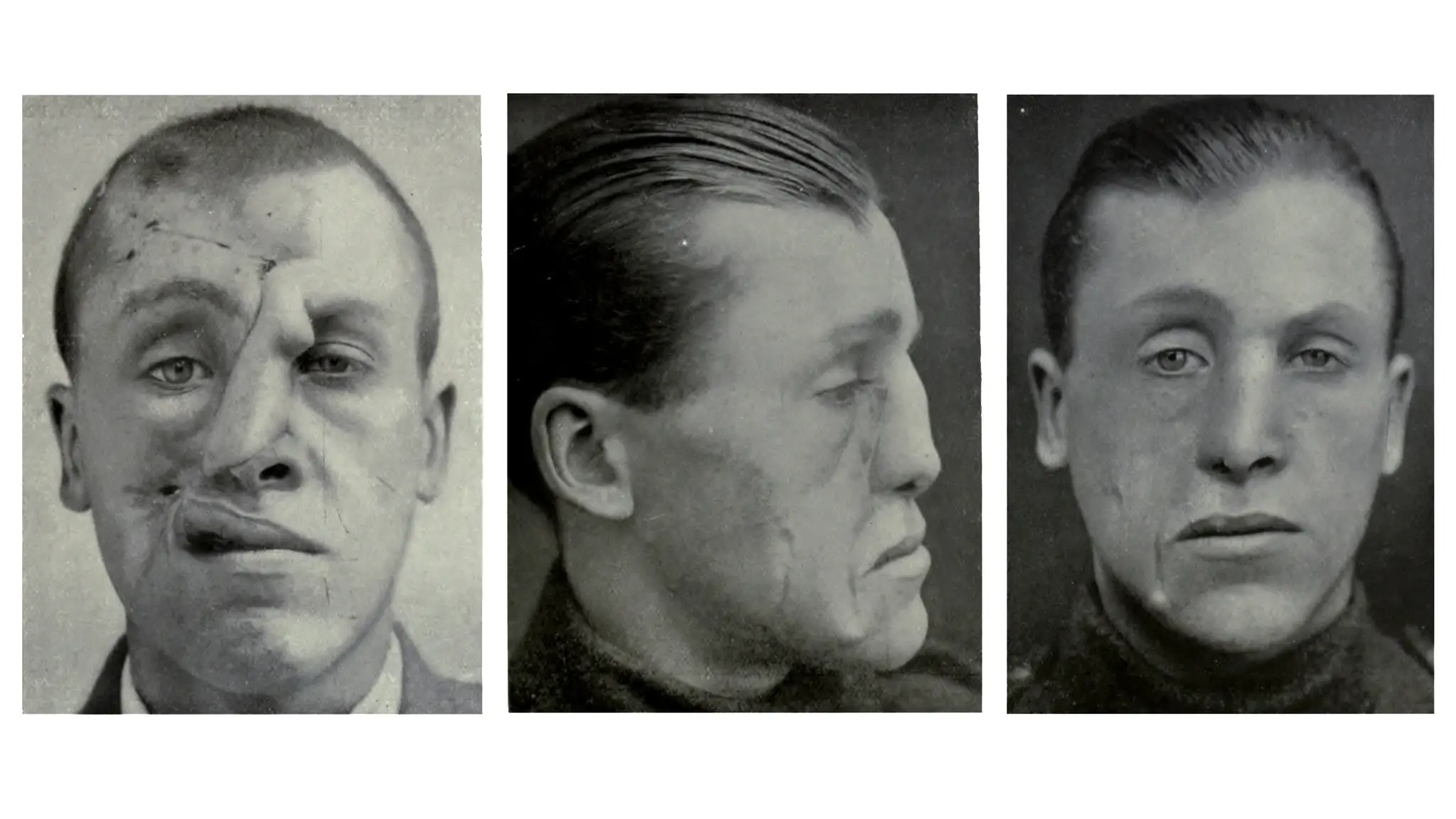

Unlike limb amputations, which had long-established protocols, facial injuries presented a unique challenge. The face is a complex structure of bone, muscle, skin, and expression. Damage to it affected not just function—speech, eating, breathing—but also a soldier’s ability to reintegrate into society. The need for a new kind of surgery became urgent.

🧠 Harold Gillies and the Birth of Modern Plastic Surgery

Enter Harold Gillies, a New Zealand-born surgeon serving in the British Army. In 1915, while stationed in France, Gillies witnessed the scale and severity of facial injuries and realized that traditional surgical methods were woefully inadequate. He returned to England and lobbied for a dedicated facility to treat facial wounds. In 1917, The Queen’s Hospital in Sidcup was established. It was the world’s first hospital devoted entirely to plastic and reconstructive surgery.

Gillies didn’t just treat wounds, he invented techniques. He pioneered the use of pedicle flaps, which involved transferring skin and tissue from one part of the body to another while keeping the blood supply intact. These methods allow surgeons to create more natural-looking reconstructions. This laid the foundation for modern facial surgery.

Military patients were central to this evolution. Their injuries were complex, their recoveries long, and their needs urgent. Surgeons had to innovate in real time, often developing new procedures mid-operation. Every patient became a case study, every success a breakthrough. Gillies treated over 5,000 soldiers at Sidcup, each contributing to the growing body of surgical knowledge.

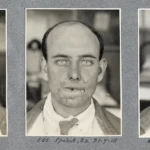

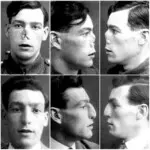

📸 Documenting the Journey: Photography and Surgical Education

The U.S. military also played a pivotal role in documenting and advancing reconstructive techniques. During the Civil War, surgeons like Dr. Gurdon Buck began experimenting with facial reconstruction, using early forms of advancement flaps and prosthetics. Buck was among the first to use clinical photography to document surgical outcomes—a practice that became essential in World War I and beyond.

We use our before and after pictures today to document journeys. As we can see, even this process had its roots thanks to the military.

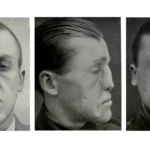

Colonel Reed Bontecou, another Civil War surgeon, systematically photographed wounded soldiers to track healing and educate future practitioners. Like the pictures we take in our office, these images weren’t just medical records—they were visual testimonies of resilience and innovation. They helped standardize procedures, refine techniques, and inspire generations of surgeons.

🧪 Innovation Through Adversity: The Guinea Pig Club

In World War II, Gillies’ cousin, Archibald McIndoe, continued the work at Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead. He treated Royal Air Force pilots with severe burns and injuries, many of whom had been trapped in flaming cockpits. McIndoe’s approach was revolutionary—not just medically, but socially.

He formed the Guinea Pig Club, a group of patients who underwent experimental surgeries and became lifelong advocates for reconstructive care. McIndoe encouraged social reintegration, inviting townspeople to interact with patients and treating them with dignity and humor. The club became a symbol of camaraderie, resilience, and the human spirit.

McIndoe also refined techniques for skin grafting, burn treatment, and psychological rehabilitation. His work laid the groundwork for modern burn units and trauma recovery programs.

🏥 The Legacy of Military Medicine in Civilian Care

The innovations born in wartime didn’t stay on the battlefield. After World War II, plastic surgery expanded into civilian medicine, addressing congenital defects, trauma injuries, and post-cancer reconstruction. Techniques developed for soldiers were adapted for children with cleft palates, accident victims, and burn survivors.

Military patients had unknowingly created a roadmap for healing. Their needs forced surgeons to think beyond aesthetics—to restore function, dignity, and identity. The field evolved from a niche specialty to a cornerstone of modern medicine.

🧬 Modern Applications Rooted in History

Today, plastic surgery encompasses a wide range of procedures:

- Reconstructive surgery for trauma, burns, and congenital anomalies

- Craniofacial surgery for birth defects and facial asymmetry

- Microsurgery for nerve and tissue repair

- Cosmetic surgery, which now benefits from decades of reconstructive innovation

Even cutting-edge procedures like face transplants and 3D-printed implants trace their lineage back to the battlefield. The ethical frameworks, surgical techniques, and patient-centered care models all stem from lessons learned treating military patients.

🧠 Psychological Healing and the Power of Identity

One of the most profound contributions of military patients was the recognition that healing isn’t just physical—it’s psychological. Disfigurement can lead to depression, anxiety, and social withdrawal. We see that as much today, here in our plastic surgery office in Charleston WV, for our patients with trauma, cancer, etc., as these historical surgeons saw it in World War I. Surgeons like Gillies and McIndoe understood this and treated the whole person, not just the wound.

Their holistic approach—combining surgery with social support, counseling, and community reintegration—became a blueprint for modern trauma care. It also helped destigmatize facial differences and promote empathy in medical practice.

🧭 Conclusion: A Legacy of Courage and Innovation

Plastic surgery owes its existence not to vanity, but to necessity. It was born in the trenches, refined in operating rooms, and carried forward by the courage of military patients who endured unimaginable pain for the sake of healing. Their stories are not just medical milestones—they are human triumphs.

As Harold Gillies once wrote, plastic surgery is not merely about restoring appearance, but about “buoying up the spirit, and helping the mind of the afflicted.” That ethos, born in wartime, continues to guide the field today.

We have compiled some pictures here of World War one plastic surgeries, battlefields, hospitals. These are the earliest plastic surgery before and afters. We hope you find them interesting in much the same way as we did.

Veterans, we salute you. We thank you.